Top Avana

"Buy discount top avana 80mg online, erectile dysfunction drugs in nigeria."

By: Lars I. Eriksson, MD, PhD, FRCA

- Professor and Academic Chair, Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Stockholm, Sweden

It is therefore important that the instructions be very precise when using this manipulation erectile dysfunction brands top avana 80mg with visa. Music does not require highly motivated participants erectile dysfunction bipolar medication buy top avana 80 mg cheap, does not direct participants to how to fix erectile dysfunction causes top avana 80 mg amex impotence after prostatectomy discount top avana 80mg free shipping specific feelings, and has been shown to produce significant effects on judgment and behavioral measures (Gorn, Goldberg, & Basu, 1993; Gorn, Pham, & Sin, 2001). However, there is significant variance in the population when it comes to music tastes, which can compromise reliability. Exposure to affectively charged videos has proven to be quite successful due to the general appeal of these stimuli (low motivation required), their easy-to-determine valence, and their higher intensity, compared to written or audio stimuli. However, as mentioned before, using a common video across participants within a given mood condition raises the possibility of confounding between affective experience and the semantic or episodic content of the video. To try to mitigate this problem, one can consider using different stimulus replicates across conditions or experiments. Another potential drawback of video-based inductions is that, compared to other procedures, exposure to videos may also facilitate hypothesis guessing and, consequently, demand artifacts. To avoid such concern, the cover story must be convincing and, also importantly, the affect manipulation check disguised. For example, Cohen and Andrade (2004) used a combined technique of video plus personal experience, in which participants were informed that the university, in order to augment its web-based teaching environment, attempted to assess the impact of audio and video stimuli transmitted through the web. Students were informed that they would watch five minutes of a video and then would perform memory and judgment recall tasks. After the video, the "memory task" instructed them to write a personal story related to the scenes watched in the clip. Videos have also been used to manipulate specific emotional states, such as anger (Andrade & Ariely, 2007; Phillipot, 1993) sadness and disgust (Lerner, Small, & Loewenstein, 2004), and fear (Andrade & Cohen, 2007b). Restricting the effect to one specific emotion may be challenging; some video manipulations can enhance more than one specific affective state at the same time. For instance, Gross and Levenson (1995) showed that an anger manipulation tended to increase disgust levels as well. As they pointed out, "With fi lms, it appears that there is a natural tendency for anger to co-occur with other negative emotions" (p. Still, videos and some combined techniques (video and personal story writing) are relatively successful affect manipulations (Westermann, Spies, Stahl, & Hesse, 1996). Physiological and cognitive antecedents of emotion the influential James-Lange theory (James, 1884) held that emotional stimuli elicited bodily responses, that is, peripheral activity such as changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and skin conductance, and that these bodily responses were translated fairly directly into conscious differences in emotional experience. While there was modest success relating "energetic" physiological responses to higher arousal negative affect (compared to lower arousal states such as sadness and guilt), there was no consistent translation of bodily responses into differential positive affect. More generally, such physiological measures do not appear to reflect essential differences in the valence of emotion (Bradley, Cuthbert, & Lang, 1993; Schimmack & Crites, 2005). One response to the failure to support the James-Lange theory was to search for other, more sensitive indicants of emotional response that could then be interpreted as particular types of emotion. Facial feedback theories identified patterns that corresponded to happiness, surprise, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust (Ekman, 1973; Izard, 1977; Kleinke, Peterson, & Rutledge, 1998). However, a meta-analysis of these studies (including those where participants were induced to adopt musculature associated with smiling and frowning) indicated that these effects were too weak to perform the central function ascribed to bodily responses in the James-Lange theory (Matsumoto, 1987). A more basic challenge to the original theory was to question the central role of bodily response to subsequent emotional experience. Schachter and Singer (1962) made significant inroads by showing (via injections of either epinephrine or a placebo) that peripheral arousal only differentiated an emotional response from merely cognitive responses. In their two-factor theory, cognitive processes played the decisive role in interpreting the arousal that was being experienced. A substantial challenge to the bodily arousal component of this theory can be seen in other research conducted at about the same time. Lazarus and Alfert (1964) asked people to watch a fi lm depicting a tribal ritual involving what appeared to be genital mutilation. However, half of those watching were given misinformation that the experience was actually not painful and that adolescents looked forward to this initiation into manhood, and significant cognitive control over arousal was observed. Subsequent research on spinal cord injured patients best supports the view that peripheral arousal is not necessary to the experience of emotion, but can intensify it (Mezzacappa, Katkin, & Palmer, 1999). Recent research on memory, for example, demonstrates the importance of such emotional experience to memory consolidation, and is, thus, consistent with evolutionary underpinnings of classical conditioning (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998). More generally, emotional response was shown to be far more under cognitive control and appraisals of experience than had been imagined. While emotional underpinnings may be somatic, and in that sense have significant evolutionary value in predisposing the body toward approach/appetitive or avoidance/inhibitory action, modern theories point to relatively few hardwired connections to discrete emotional states (Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987; Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988).

A behavior will be incorporated into risk estimated to erectile dysfunction herbal buy generic top avana 80mg on line erectile dysfunction doctors long island generic top avana 80mg on-line the extent to erectile dysfunction at age 35 cheap top avana 80mg on-line erectile dysfunction lack of desire buy top avana 80mg on line which a behavior is perceived to be diagnostic. The level of fear follows an inverted-U shaped curve, with low and high levels of fear backfiring. Emotions such as hope are Emotions of the same savored, while those such as valence do not lead to anxiety are not. Increase the salience of alternate information that consumers could use to make risk judgments (such as the accessibility of their own behavior). It may be easier to frame communication in terms of a "close other" to reduce defensive tendencies Consider the frame surrounding estimates. Identify roles of fear, hope, regret and others in the decision calculus that consumer used to trade off a current affective state over a future affective/ physiological state. Examine the interplay between affective and cognitive and physical and mental health. Increasing perceptions of diagnosticity increase the likelihood that if a symptom is identified it will enter through to risk judgments. Increase communication about the diagnosticity of various symptoms and behaviors for a disease. Negative Affect Discrete emotions Contextual Alternative information Response alternatives Measure subjective symptoms using subjective response scales. Proxy information Consumers construct rather than retrieve judgments using contextual cues making their risk judgments tensile and easily changed. While survey methodologists can use this information to improve response accuracy, social marketers can use this information to increase estimates of risk so as to encourage behavior change. Depressives are less prone to self-positivity; optimists are less likely to update risk estimates. More controllable events are more prone to self-positivity and have a higher likelihood of risk judgments translating into behavior. The more ambiguous the symptom, the less likely it will be incorporated into judgments, and the more likely it will be prone to context effects. Consumers may use the presence of an extreme symptom on an inventory to categorize themselves as "not at risk. Separate analyses by individual difference variables and identify different methods to increase compliance towards a desirable behavior for different segments. Some prescriptions for theory Selected prescriptions for practice Some open questions for future research Identifying other individual difference variables that moderate the extent of selfpositivity and those that moderate the risk perception-behavior link. These could include contextual cues, advertising, framing effects and other methods. Th ree primary phenomena highlight the motivational factors affecting health risk perceptions: self-positivity (or unrealistic optimism), social desirability, and self-control. Self-Positivity Bias To accommodate a need for mental well-being and self-enhancement, people might be unrealistically optimistic in their own risk perceptions (Taylor & Brown, 1988). This motivationally driven bias, referred to as the self-positivity bias (Ragubir & Menon, 1998), is widely documented in the health literature and can affect risk perceptions in several ways (for a review see Taylor, 2003; Taylor et al. The self-positivity effect was first tested in the domain of health risk perceptions by Perloff and Fetzer (1986) and has since become a topic of mainstream interest in consumer psychology (Chandran & Menon, 2004; Keller, Lipkus, & Rimer, 2003; Lin, Lin, & Raghubir, 2003b; Luce & Kahn, 1999; Menon, Block, & Ramanathan, 2002; Raghubir & Menon, 1998, 2001). Shepperd, Helweg-Larsen, and Ortega (2003) found that self-positivity manifests regardless of time, as well as whether or not one has experienced related event. Self-positivity leads people to perceive themselves as being less risk-prone than known or similar others in the same risk group. Self-positivity effects may be due to an overall desire to feel happy (Raghubir & Menon, 1998) and to maintain or enhance self-esteem (Lin et al. They argued that if people can attribute a lower risk of a negative event to their own actions, which is more likely to be true for controllable (vs. If consumers assume that they are less at risk than others, they may tune out preventative advertising directed to them (Diclemente & Peterson, 1994; Fisher & Fisher, 1992). Self-positivity could also promote complacency (Skinner, 1995) rather than effective goal-relevant behavior (Weinstein 1989). On the one hand, self-positivity motivated by self-enhancement may have negative effects on health outcomes through a lack of attention or defensiveness towards another wise relevant risk. Self-enhancement motives operating through the same self-positivity effect could create an illusion of positivity that might provide a stress-buffering resource to deal with information that conveys a relevant risk (Taylor et al.

Buy cheap top avana 80 mg. Hypnosis for Erectile Dysfunction (ED).

He described the clinical syndromes associated with Francisella infection and named it "tularemia impotence natural remedy purchase top avana 80 mg on-line. However impotence nerve effective top avana 80 mg, as mounting scientific data supported the creation of a new genus for this remarkable pathogen impotence 35 years old buy 80 mg top avana with mastercard, this bacterium was assigned to erectile dysfunction pills available in india discount top avana 80mg amex its own genus and the name Francisella was proposed in tribute to Edward Francis. F tularensis is considered to have four subspecies: (1) tularensis, (2) holarctica, (3) mediasiatica, and (4) novicida. F tularensis subspecies holarctica typically causes a less clinically severe disease than subspecies tularensis, but has been documented to cause bacteremia in immunocompetent individuals. Photograph: Courtesy of Dr Larry Stauffer, Oregon State Public Health Laboratories, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, Public Health Image Library, Image 1904. Tularemia been isolated in the central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union, and it appears to be substantially less virulent in a rabbit model compared to F tularensis subspecies tularensis. F tularensis subspecies novicida, also referred to as F novicida, is believed to be avirulent in healthy humans. Reported cases associated with this subspecies usually involve patients with other underlying health conditions. Another closely related species, Francisella philomiragia, has also been described as a human pathogen. Healthcare providers need to understand the range of possible presentations of tularemia to use diagnostic testing and antibiotic therapy appropriately for these infections. Most cases of naturally occurring tularemia are ulceroglandular disease, involving an ulcer at the inoculation site and regional lymphadenopathy. Variations of ulceroglandular disease associated with different inoculation sites include ocular (oculoglandular) and oropharyngeal disease. Occasionally patients with tularemia present with a nonspecific febrile systemic illness (typhoidal tularemia) without evidence of a primary inoculation site. Pulmonary disease from F tularensis can occur naturally (pneumonic tularemia), but is uncommon and should raise suspicion of a biological attack, particularly if the cause is not readily discernable and significant numbers of cases are diagnosed. Because of the threat of this microorganism as a biological weapon, clusters of cases in a population or geographic area not accustomed to tularemia outbreaks should trigger consideration for further investigation. An investigation should yield the likely cause of the outbreak, which could be varied (exposure to infected animals, arthropod borne, etc). By determining the source of the outbreak, it may be possible to implement control measures, such as water treatment or use of an alternative water supply if the outbreak is traced to a waterborne source. Epidemiology F tularensis subspecies tularensis (type A) is the most virulent subspecies and found predominantly in North America. This subspecies has recently been genetically subdivided into two subpopulations, A. The subpopulations are distinct in mortality rates, geographic distribution, transmission vectors, and hosts. In the United States, 90 to 154 cases of tularemia have been reported yearly from 2001 to 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human outbreaks, which are often preceded by animal outbreaks, are seasonal, with the highest incidence in late spring, summer, and autumn. F tularensis is unique in its ability to adapt to a wide range of environmental, host, and vector conditions, and it can be categorized into two distinct transmission cycles involving different hosts and arthropod vectors. The cycle of disease is commonly associated with a subspecies, with type A commonly associated with the terrestrial cycle and type B commonly associated with the aquatic cycle. Direct Contact In 1914, a meat cutter with oculoglandular disease, manifested by conjunctival ulcers and preauricular lymphadenopathy, had the first microbiologically proven human tularemia case reported. From March through April 1982, 49 cases of oropharyngeal tularemia were identified in Sansepolcro, Italy. The infected individuals had consumed unchlorinated water, and a dead rabbit from which F tularensis was isolated was found nearby. Instances of transmission from the bites or scratch of a cat, coyote, ground squirrel, and a hog to humans were documented more than 80 years ago. The hundreds of pneumonic cases likely resulted from 288 contact with hay and dust contaminated by voles infected with tularemia. F tularensis was later isolated from the dead rodents found in barns, as well as from vole feces and hay.

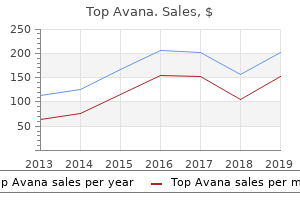

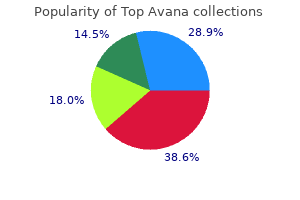

Data collection was suspended on September 11 erectile dysfunction statistics in canada order top avana 80mg line, 2001 impotence icd 9 cheap top avana 80mg with visa, before oversample interviews of the four target audiences had begun erectile dysfunction causes in young men cheap top avana 80mg otc. However erectile dysfunction after drug use best 80 mg top avana, the campaign failed to convince those with negative opinions to think otherwise. Between September 1999 and August 2001, the number of adults with favorable opinions of Philip Morris increased from 26% to 38%, but unfavorable opinions were unchanged (41% to 42%). Unaided recall of television advertisements for Philip Morris companies 200 peaked at 45%, and advertisement awareness was associated with more favorable impressions of the sponsor. Hostility toward Philip Morris and the industry it represents appears to be softening. In an annual survey of corporate reputations that evaluates products and services, financial performance, workplace environment, leadership, social responsibility, and emotional appeal of the 60 most visible U. Prominent political and public health figures convene a press conference to announce a lawsuit to ban the advertisements, subpoena all records related to the effort, and propose legislative efforts to increase tobacco excise taxes to pay for new antismoking advertisements. Popular daytime talk show host devotes an entire week of shows to ask the question, "who are the people of Philip Morris Popular nighttime talk show host attacks the advertising campaign by producing mock advertisements with the tagline, "The people of Philip Morris-Sick, fat, drunk & dead. In 2003, its reputation surpassed only those tainted by the specter of bankruptcy or criminal indictment. Key segments were targeted, including African Americans, Hispanics, opinion leaders, and active mothers. Public opinion research showed high overall awareness of the campaign (45% unaided recall). Among those with prior existing negative opinions of Philip Morris, opinions remained unchanged. However, adults without prior existing opinions of Philip Morris revealed an increase in positive associations with the company. African Americans, in particular, showed an increase in favorable opinions as a result of the integrated campaign. Tobacco industry documents should be examined to learn 202 what strategies were used to accomplish these goals, to aid the design of effective tobacco control campaigns. Studies have found that both adults and adolescents perceive the tobacco industry as dishonest and hold it in low esteem. In response to these concerns, tobacco companies have moved aggressively toward corporate public relations efforts aimed at building the public images and brand identities of their firms, spending hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. This chapter examines two such areas whose impact has been studied through research: corporate sponsorship and corporate advertising. Research reviewed in this chapter suggests that corporate image campaigns have been successful in reducing negative perceptions of the tobacco industry. While research investigating the role of tobacco sponsorship in reducing negative perceptions has not been done, in other industries research shows that sponsorships build positive brand associations and reduce negative brand associations. Evidence for the effects of corporate advertising on perceptions does exist for the tobacco industry. Studies reviewed in this chapter have found that corporate advertising reduces perceptions among adolescents and young adults that the tobacco companies are dishonest and culpable for adolescent smoking, and, among adults, increases favorability ratings for the individual company, such as Philip Morris. Also important are the effects of corporate sponsorship and corporate advertising on the sale and use of tobacco products, Monograph 19. The Role of the Media intentions to start smoking, intentions to quit smoking, and susceptibility of smokers to claims about "lower risk" cigarettes. More research is needed to determine the effects of other forms of corporate advertising and tobacco sponsorship on smoking intentions and behavior. In industries other than tobacco, increased consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility and other favorable associations with a company have been linked to increased interest in and sales of products made by those companies. Perhaps most important are the effects that softening negative attitudes and improving public image perceptions of cigarette companies may have on legislation, jury awards, public support, and consumer activism. Some evidence exists that patrons of corporate sponsors have felt an obligation, or even felt compelled, to voice support for the tobacco sponsor in opposing smoking bans. Industry documents show that the tobacco industry motives for youth smoking prevention programs include discouraging legislation that restricts or bans tobacco sales or marketing activities.

References:

- https://books.google.com/books?id=JDi6DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA140&lpg=PA140&dq=Leigh's+Syndrome+.pdf&source=bl&ots=KWv_DBS_ds&sig=ACfU3U044zKNDIELiiOeVfwBKzJ8cqcfww&hl=en

- https://www.worlddiabetesfoundation.org/sites/default/files/WDF09-436%20Community%20Diabetes%20Control%20Participant%20Booklet%201.pdf

- http://www.psychiatry.ru/siteconst/userfiles/file/englit/A.%20Hibbert,%20A.%20Godwin,%20F.%20Dear%20-%20Rapid%20Psychiatry%20(PDF,%20823%20Kb).pdf

- https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a115904.pdf