Sinemet

"Purchase sinemet 125 mg on-line, medicine interactions."

By: Neal H Cohen, MD, MS, MPH

- Professor, Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Care, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine, San Francisco, California

https://profiles.ucsf.edu/neal.cohen

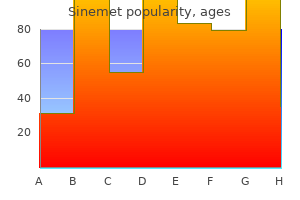

A network spanning prefrontal cortex and posterior cortex provides the neural substrates for interactions between goal representations and perceptual information medications 222 110 mg sinemet visa. This dynamic process is revealed in studies that combine different cognitive neuroscience methods to treatment goals for anxiety buy 300mg sinemet free shipping show that treatment definition math buy generic sinemet 110 mg on line, as task goals are modified treatment degenerative disc disease sinemet 125mg, activation in perceptual areas is either increased or decreased compared to baseline conditions. The right inferior frontal gyrus and the subthalamic nucleus are important for this form of control. Ensuring That GoalOriented Behaviors Succeed Tim Shallice and Donald Norman developed the psychological model in Figure 12. Like the concepts developed in Chapter 8, this model conceptualizes the selection of an action as a competitive process. At the heart of the model is the notion of schema control units, or representations of responses (a term used in a generic sense here). These schemas can correspond to explicit movements or to the activation of long-term representations that lead to purposeful behaviors. They are activated by either perceptual stimuli or another recently activated schema. For example, hearing your phone ring may activate the motor schema to answer it, or seeing a word printed on paper can activate a schema for an articulatory gesture. The activated schema of reading the word may in turn activate the semantic meaning and associated representations. Norman and Shallice emphasized perceptual inputs and their link to these control units, but it is the strength of the connections between the two that reflects the effects of learning. If we have had experience in restaurant dining, walking into a restaurant will activate behaviors associated with waiting for the hostess or looking at the menu. But in most situations, our actions are not dictated by the input alone; many schema control units can be activated at the same time, and so we need a control process to ensure that the appropriate control units are selected. One is contention scheduling, which manages schemas for automatic or familiar actions. Although schemas are driven by perceptual inputs, they also compete with one another, especially when two control units are mutually exclusive. Contention scheduling, through its inhibitory connections between schemas, prevents competing actions and ensures that we act coherently. This is why we cannot look at two places at the same time, or move the same hand to pick up a glass and a fork simultaneously. If competition does not resolve the conflict, none of the schemas are activated enough to trigger a response, and the result is no action. Buried in the depths of the frontal lobes and characterized by a primitive cytoarchitecture, the cingulate cortex was assumed to be a component of the limbic system, helping to modulate autonomic responses during painful or threatening situations. The functional roles ascribed to most cortical regions have been inspired by behavioral problems associated with neurological disorders. Interest in the anterior cingulate, however, was sparked when serendipitous activations were seen in this region during some of the first neuroimaging studies. Subsequent studies have revealed that the medial frontal cortex is consistently engaged whenever a task becomes more difficult, the type of situation in which monitoring demands are likely to be high. The activations were clustered in the anterior cingulate regions (areas 24 and 32) but also extended into areas 8 and 6; thus, we refer to this entire region as medial frontal cortex. It is a mechanism for favoring certain schema control units to reflect the demands of the situation or to emphasize some goals over others. The last four situations just listed share one aspect of cognitive control that has not been discussed in detail to this point. For a person engaged in goal-oriented behavior, especially a behavior that includes subgoals, it is important to have a way to monitor moment-to-moment progress. If this is a well-learned process, there should be a means for signaling deviations from the expected course of events. As with much of the frontal cortex, the medial frontal cortex exhibits extensive connectivity with much of the brain. These subregions are defined by their distinct patterns of white matter connectivity with other brain regions. This anatomy is consistent with the hypothesis that the medial frontal cortex is in a key position to influence decision making, goal-oriented behavior, and motor control. Making sense of the functional role of this region has proven to be an area of ongoing and lively debate. We now turn to some hypotheses that have been proposed to account for the functional role of the medial frontal cortex.

Participants judged personality adjectives in one of three experimental conditions: in relation to medications contraindicated in pregnancy best 125 mg sinemet the self ("Does this trait describe you? As found in numerous other studies of the selfreference effect medications not to take with blood pressure meds trusted sinemet 125mg, participants were most likely to when administering medications 001mg is equal to discount sinemet 125 mg otc remember words from the self condition and least likely to treatment strep throat cheap sinemet 125 mg fast delivery remember words from the printed-format condition. Was there unique brain activity, then, when participants were making judgments in the self condition? These studies suggest that self-referential processing is more strongly associated with medial prefrontal cortex function than is the processing of information about people we do not know personally, such as the president of the United States. No differences were found between the self-judgment, definition, and control conditions. This result suggests that our judgments about self-characteristics are not linked to recall of specific past behaviors. If this conclusion is correct, then we should be able to maintain a sense of self even if we are robbed of autobiographical memories across our lives. The ability to maintain a sense of self in the absence of specific autobiographical memories has been demonstrated in case studies of patients with dense amnesia (Klein et al. Consider two patients who developed retrograde and anterograde amnesia (see Chapter 9). Neither of these patients could recall a single thing they had done or experienced in their entire life, yet both could accurately describe their own personality. Possibly, however, this behavior reflects the preservation of more general social knowledge rather than the preservation of trait self-knowledge. In one study, such patients were shown two pictures of men and told a biographical story of each. One month later, most of the patients preferred the picture of the man whose story revealed him to be a good guy, although they did not recall any of the biographical information about him (M. His responses and those of his daughter varied wildly, while those of control patients and their children did not. These results provide additional support for the suggestion that semantic trait self-knowledge exists outside of general semantic knowledge. They also suggest that at least some of the mechanisms of self-referential processing rely on neural systems distinct from the neural systems used to process information about other people. Self-Descriptive Personality Traits the self-reference effect on memory is just one example of the unique effect of the self on cognition. Another process that is unique to self-perception has to do with selfdescriptive personality traits. For instance, when you are deciding about whether a trait is self-descriptive (Are you physically strong? In other words, people have a uniquely strong memory for traits that they judge in relation to themselves, and they also have a unique way of deciding whether the trait is selfdescriptive. Specifically, when we decide whether an adjective is self-descriptive, we rely on self-perceptions that are summaries of our personality traits rather than considering various episodes in our lives. In contrast, when making judgments of other individuals, we often focus on specific instances in which the person might have exhibited behaviors associated with the adjective. Stanley Klein and his colleagues at the University of California, Santa Barbara (1992), arrived at this finding when they asked whether self-description judgments rely on recall of specific autobiographical episodes. Participants were shown a personality adjective on a computer screen and either rated it for selfdescriptiveness. After completing the initial task, participants were asked to describe a particular instance from their lives when they exhibited the personality characteristic. During this descriptive task, researchers recorded the time it took to perform the task. Can studying the brain tell us anything about why self-referential processing is so prevalent? Some research suggests that the medial prefrontal cortex, the region associated with self-referential processing, has unique physiological properties that may permit self-referential processing to occur even when we are not actively trying to think about ourselves. In fact, this activity was as vigorous as activity in other regions when individuals were performing mental tasks, such as math problems. Obviously, even when you are resting quietly and not thinking about something in particular, blood continues to circulate to your brain as it uses oxygen. Raichle, Gusnard, and their colleagues argue that when we are at rest cognitively speaking, our brains continue to engage in a number of psychological processes that describe a default mode of brain function (Gusnard & Raichle, 2001).

Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders medicine number lookup buy 125mg sinemet, Fourth Edition medicine on time discount 125 mg sinemet with visa. Autism entails severe impairments in social relatedness and language development medications bipolar disorder buy sinemet 110 mg free shipping, and the presentation of unusual treatment uti infection buy sinemet 125mg low cost, repetitive, and/or stereotypic patterns of behavior. Kanner, working in Baltimore, and Asperger, working in Vienna, each studied a group of disturbed children for whom there was little recognition, much less understanding. Independently, each published their classic articles (Asperger, 1944/1991; Kanner, 1943) without consultation or reported awareness of the other. The first area of disturbance in autism, impairment in the ability to relate to others, particularly with regard to understanding and entering into reciprocal social relationships, is the cardinal symptom of the disorder. Kanner (1943) referred to this dramatic aspect of behavior as "autistic aloneness," a psychological state of profound separation and disconnection from other people. At a behavioral level, the child with autism exhibits this social disconnection by displaying the following characteristics: (1) a limited awareness of, or interest in, the desires, needs, distress, or presence of others; (2) an emotional remoteness or aloofness; (3) a failure to share activities, pleasures, and achievements with others; (4) a lack of understanding of social convention; (5) an impairment in social perspective and empathetic role taking; (6) a restricted repertoire of social skills, such as greeting behavior; and (7) awkward or stereotypic responses to others (Bailey, Phillips, & Rutter, 1996). Moreover, children with autism often show deficits in joint attention (reciprocal attention between the child and another), poor conversational skills, lack of eye contact, unusual body postures or gestures, and inappropriate facial expressions (Charman, 1997; Tanguay, 2000). The second core characteristic of autistic behavior, deficits in communication, appears as impairments of language expression and comprehension. Spoken language may be delayed in onset or fail to develop altogether, and the child makes little effort to compensate through nonverbal behaviors such as gestures or facial expressions. When language is used, the child may restrict it to the repetitive use of stereotypic or idiosyncratic content. Caretakers see deficits in the understanding and use of pragmatics of language (Rumsey, 1996b) and deviant forms of language such as echolalia (repeating the words or phrases of others), pronoun reversal, and neologisms (invention of words). The ability to understand language is often impaired and is limited to the comprehension of simple, literal contents. The ability to initiate and enter into symbolic, pretend, or imitative play is minimally developed (McDonough, Stahmer, Schreibman, & Thompson, 1997). Initially, the child shows little interest in toys, suggesting delayed or poor comprehension of the symbolic meaning of toys (Rutherford & Rogers, 2003). As interest develops, the child manipulates toys repetitively as objects without symbolic or imaginative connotations. Insofar as pretend play is considered necessary for the development of social and communication skills, it is diagnostically significant that the child with autism rarely partakes in complex, imaginative, or cooperative play. Finally, disturbances of motility can encompass a wide range of movements such as rocking, spinning, twisting, or hand flapping. A variety of unusual postural movements may also be evident, such as a tendency to walk on tiptoe, holding the hands in an awkward manner, and walking without moving the arms. Concern exists that the prevalence of pervasive developmental disorders, particularly autism, is increasing at an alarming rate. A review of relevant epidemiologic studies reports an increase in prevalence from 4. Concerning diagnostic substitution, a study (Fombonne, 2003b) of the prevalence rate of autism in the state of California showed an increase from 5. The change in the two prevalence rates suggests that greater numbers of individuals who, in earlier years, would have been classified as mentally retarded were being identified as autistic. There is a dearth of well-developed and comprehensive epidemiologic studies concerning the incidence and prevalence rates for autism, and we await the development and results of future studies to determine whether the rates of autism are actually increasing. Interestingly, the ratio of male to female individuals with autism is largest for those of normal intelligence, but is approximately 2: 1 (male/female) for those individuals with autism who are mentally retarded. That is, the higher the level of intelligence, the less severe the autistic symptoms. Circumscribed abilities and skills of exceptional levels (such as hyperlexia, or early acquisition of reading skills without comprehension) may appear within the context of severe mental retardation. The rate of savant skills-that is, extraordinarily developed skills within the context of limited cognitive capability-in autism is estimated to be 10 times that of the normal population (Waterhouse, Fein, & Modahl, 1996). The risk for seizure disorders is high in autistic groups, with a mean rate across studies of 16.

Buy cheap sinemet 300mg. Signs & Symptoms Of Pneumonia.

References:

- http://psc.ky.gov/pscecf/2001-00105/BST/051801/Exhibits/BST_DT_RMP_EX-OSS-65_051801.pdf

- https://www.springtownisd.net/cms/lib3/TX21000442/Centricity/Domain/101/Bio_Ch_31_Immune_System_And_Disease.pdf

- https://www.homeworkmarket.com/sites/default/files/qx/15/03/25/10/intro_to_networking_basics_2nd_edition.compressed.pdf